Some results from Site 292.

We have found our ancient village!

Over the course of a week or so Rafeeq, Ali, and I have collected 134,400 readings of the strength and direction of the Earth’s magnetic field from each of two sensors on our GeoScan FM-256 gradiometer at Site 292. The sensors are positioned on top of one another at either end of 0.5m tube. The sensor at the top serves as effectively a ‘background reading’ while the sensor at the bottom of the tube, closer to the ground, has the same background, plus it measures the effect of buried soils, features, and artifacts (including archaeology!) in roughly the top meter of soil.

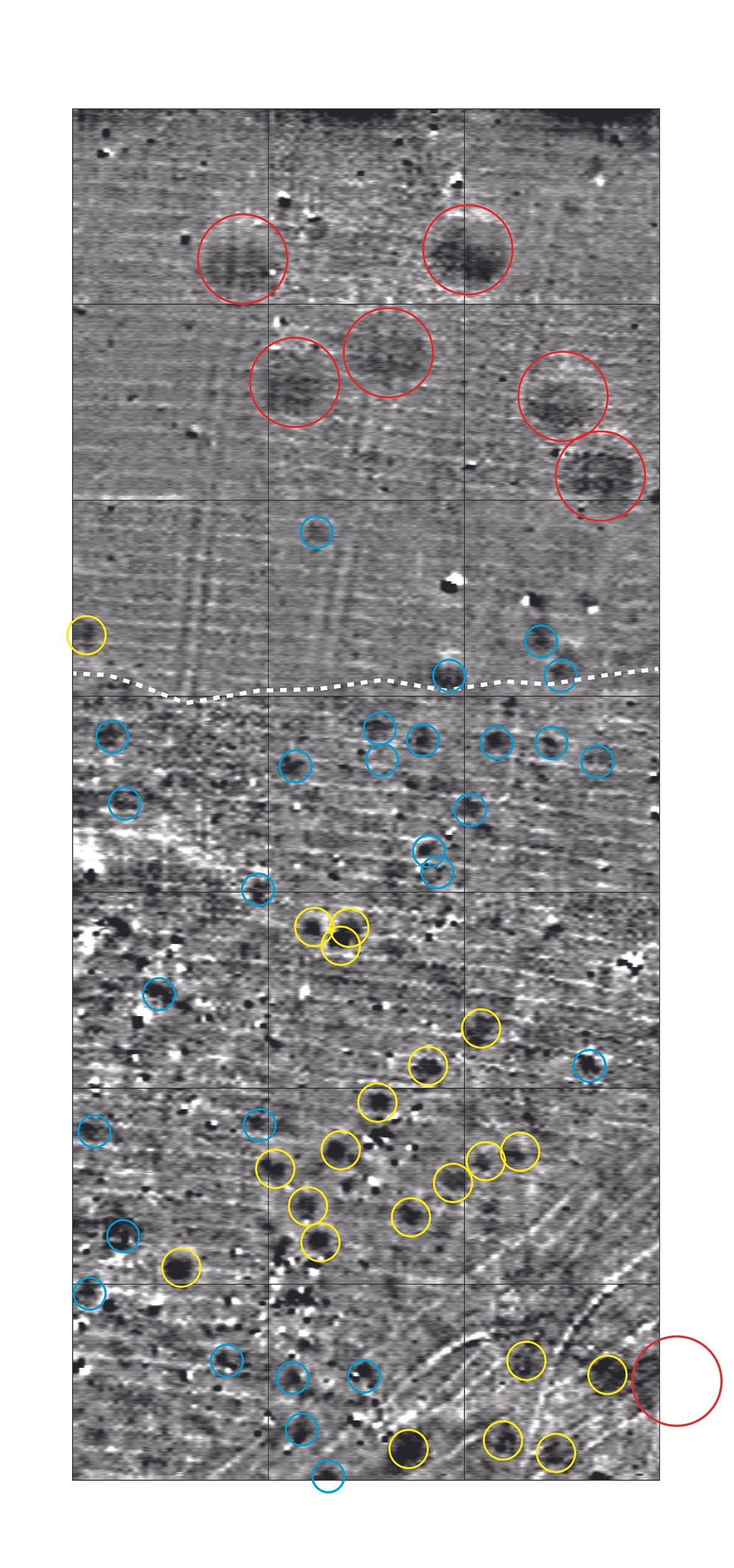

As we collect data, the bottom sensor reading is subtracted from the reading of the top sensor and we see the gradient between the two which has the effect of cancelling out the Earth’s magnetic field leaving only the effects caused by things at or below the surface. The figure below shows a map of Site 292 creating by assigning each of the 134,400 readings a grey scale value. Strongly positive and negative magnetic readings are black and white, while the majority are a shade of grey.

I know this looks like a mess. It is not easy to read the magnetic field gradiometry map. How ever, I’ve been reading these maps from the FM-256 for 25 years now, so I’m able to make pretty reasonable guesses at what we are seeing here. Each pixel in our map represents an area of 12.5 cm x 12.5 cm, and the entire map covers an area of 60m (east-west) by 140m (north-south). So our map is covers just over two acres of land.

The key to interpretation is distinguishing between the “signal”, that is the features we are interested in – ancient features, from the “noise” which is either underlying geology or, more importantly here, the signs modern agricultural practices or modern trash.

All the white lines running roughly east-west are plow scars, and the long parallel linear features running roughly north-south are truck tracks. Likewise, in the bottom right corner (southeast) are tracks from a modern tractor. We know this because we can see them on the surface. These are noise. We can ignore them in our analysis. The plow scars are deep (c. 15cm) so they are prominent. The tire tracks are not and they seem to “disappear” about halfway down from the top of the map because they are only visible in the quieter part of the map.

As you can imagine a modern field has quite a bit of modern trash in it. Plastic bottles, pieces of rubber tires, and other non-ferrous metal have no effect on the gradiometer because they are not magnetic. However, small pieces of iron or steel do and each of the yellow circles represents what is most likely a modern piece of metal. A few might be ancient, but these tend to have a weaker signal that nails, screws, pieces of iron wire, bits of broken plows, and other farming debris.

Finally, at the top of this map – the Noise Map – are three large black features at the very northern edge of the survey area. I didn’t draw them as circles because they are iron poles for carrying electrical wires Despite the fact that they are over 5m away from the edge of our survey area, and they are only about 15cm in a diameter, they are strong magnets that cast a “shadow” way out of proportion to their size. In fact, we can’t survey any closer to them because they would swamp the ancient signal with their noise.

So what’s left after we account for the noise, most likely are the remains of the ancient Site 292.

The seven red circles represent very large pits (roughly 8-9 m in diameter). They don’t appear to be modern because the signal is weak and there is almost no metal in them. We have found clusters of such pits before and they were probably storage pits in the Neo-Assyrian period, possibly for grain. There is one possible storage pit in the southeast corner, but I have my doubts given its proximity to other ancient features. The yellow circle and blue circles are slightly smaller pit-like features. They may have been household storage or trash pits, or even postholes to hold timbers for house construction, although this is unlikely since the Assyrians tended to build in mudbrick. The yellow features are larger than the blues ones, but this may or may not turn out to be important in terms of their ancient functions.

One important feature is that the northern part of the site has far less ancient material and, in general, is a more monotone grey in the gradiometry map, suggesting that it may actually be outside of where people were living day-to-day. The dashed white line is roughly the edge of what seems to me to be the “household area” and beyond it to the north may have been used for other purposes. If the red circles are for grain storage, they would have held a lot of grain!

We don’t see any evidence of mudbrick walls or stone wall foundations, but this is not at all surprising given that this was a very small place occupied for maybe a century or so that was abandoned 2,600 years ago and has been intensively farmed since them. A few of the red, yellow, and blue circles will be our targets for excavation in 2026 when we can really start getting into the details of what the Neo-Assyrian inhabitants of 292 might have been doing all those years ago in this forgotten place.